The Seasoned Scratcher

hardmath123 + technoboy10 · Sunday, August 16, 2015

Your hosts for the evening are

Hardmath123andtechnoboy10from Scratch. Together, we have over 13 years of experience with Scratch and the computer science world beyond.

So you think you’re a Scratch expert. You know the ins and outs of Scratch like the back of your hand. You may even have hacked around with the Scratch source code.

But you want something new. You want to learn more, explore, and discover. And you don’t know where to start. Everyone you ask gives you their own advice.

Here’s ours.

Which language should I learn?

The eternal question. A lot of people define themselves by the programming languages they use. People have very strong, emotional opinions about these things. The truth is, in the big picture, you can get most things done with most languages.

So before you pick a language, here’s a piece of advice: don’t collect languages, collect paradigms (that’s CS for “big ideas”). Once you know the big ideas, learning a new language should take you at most a weekend. Paradigms stay the same; they just show up in different languages hidden in a new syntax.

Having said that, here are the big ideas we think you should look at.

Functional programming is programming with functions. That means, in a way, that you’re more focused on reporter blocks than stack blocks. You don’t assign to variables much; instead of changing data in-place, you create copies that have been modified.

A lot of people think functional programming is impractical when they first get started—they don’t think you can get useful things done, or they think functional languages are too slow. Paul Graham, founder of Y Combinator (a Silicon Valley start-up which has more money than you want to know about) wrote this piece on how his company very successfully used a functional language called Scheme to “beat the averages”.

Scheme is one of the oldest languages around. It started off as an academic language used in MIT’s AI labs but over decades has evolved into a more mainstream language.

Many people have written their own versions of Scheme. The most popular one, and the one we recommend, is Racket, which was built by an academic research group but used by everyone—even publishers of books. It comes with a lot of built-in features.

The best book to learn Scheme (and the rest of computer science) is The Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs, aka SICP. It’s free to read online. Another good one is The Little Schemer and its sequel The Seasoned Schemer.

If you want to learn functional programming but still want Scratch-ey things like blocks and sprites, learn to use Snap!. Snap! is Scratch with the advanced Scheme features thrown in.

(Bonus: Here’s Brian Harvey, the creator of Snap!, on why Scheme should be taught.)

If you want to know more about Snap!, ask us on the forum thread.

Object-Oriented Programming is based on the idea of grouping data and functions under structures called “objects”. A lot of languages provide object-oriented features, and so you’re likely to run into the ideas no matter what you choose to do.

The classic object-oriented language is Smalltalk—-if you recall playing with the Scratch 1.4 source code, you were writing in Smalltalk. Smalltalk is an old language and isn’t used by anyone anymore. However, its legacy lives on: much of its syntax and some of its ideas are evident in Objective-C, the language in which you write iOS and OSX apps.

Smalltalk preached prototyping, a special kind of object-oriented programming where objects come out of “factories” called prototypes. You literally make a copy of the prototype when you make a new object. Smalltalk let you treat prototypes as objects themselves. It was very meta. This tradition lives on in JavaScript’s object-oriented style. JavaScript is the programming language of the web: originally designed for making webpages interactive, but now used for desktop software as well using Node.js.

The other kind of object-oriented programming is based on classes, which are pre-defined kinds of objects. Your program is a list of definitions for classes, and right at the end you create some instances of the classes to get things done. This pattern is the focus of the AP Computer Science course, which teaches you Java (more on this later). Java was widely used in industry for many years, and is still popular (though less so than before).

Statically Typed Languages are languages which care a lot about what kind of thing your variables are. In Scratch, you can put a string into the addition reported block and not have horrible things happen to you. Scratch isn’t statically typed.

In a statically typed language, you will be warned that you can’t add a string and a number even before you try to run the program. It will refuse to let you run it. For huge codebases managed by hundreds of programmers in a big company, this helps prevent silly errors. Though static typing probably won’t help you much on a day-to-day basis, the ideas are worth learning about and you should eventually get familiar and comfortable with the paradigm.

Java, as mentioned before, is statically typed. Other such languages are Mozilla’s Rust and Google’s Go-lang. A recent trend is to add static typing onto JavaScript, because plain old JavaScript is not very type-safe. You may have heard of TypeScript by Google or Flow by Facebook.

The C programming language is also statically typed. C is extremely low-level. It gives you a lot of control over things like memory use, the operating system, hardware, networking, and processes. This lets you write very efficient programs, but also makes it difficult to learn. It’s useful to have a working knowledge of what the C compiler does, and how assembly languages work. As such, learning C won’t teach you as much of the mathematical side of computer science as the practical side.

Finally, Haskell is an old academic language that is making a serious comeback. Haskell is statically typed with a very advanced type system. It is also functional. It has a lot of neat language features, but is not very beginner-friendly for a variety of reasons.

Logic programming or declarative programming is a completely different outlook on programming. Rather than telling the computer how to do something, you tell it what to compute and the computer tries all possible inputs until something works—-in a clever and efficient way, of course. You can use it to solve a Sudoku by explaining the rules of the puzzle without giving any hints on how to solve it.

It looks like the computer is reasoning on its own, and in fact logic programming is closely related to automatic proof generation.

Logic programming is mainly an academic thing with not too many practical applications in the Real World™. One application is database querying with languages like SQL, which try to find all elements in a data base which satisfy some criteria.

The popular languages of this paradigm are Prolog and Mercury.

We mention logic programming here only to give you some idea of what other paradigms are out there. If you learn functional programming with SICP (above), you’ll learn the basic ideas. As such, don’t worry too much about learning logic programming unless you’re really interested in this stuff. You won’t find yourself writing any “practical” code in Prolog.

Other well-known books on this material are The Reasoned Schemer and The Art of Prolog.

Having said all that, here’s a recap of the languages you might care about, what they’re good for doing, what paradigms they try to embrace, and what we want to say about them.

Snap! is just a step up from Scratch. The motto was “add as few new things as possible that let you do as many new things as possible”. It’s a great program with a nice community behind it, and can teach you a lot of CS.

Scheme is like a text-based Snap!. Though there isn’t too much “real-world” software written in Scheme, it’s certainly not “impractical”. There exist popular social networks (Hacker News) and music notation software (LilyPond) running on Scheme. Scheme will teach you to think in a new way.

Python is a relatively easy language to learn after Scratch for most people. Its syntax is supposed to resemble English. Python comes with a lot of batteries included: there are modules that let you do many cool things. It’s the most popular language out there for programming websites, and along with IPython and sage/scipy/numpy/matplotlib, it’s used in the scientific community. Python is good for automating some quick tasks (“I want to save all Wikipedia articles in this category as HTML files in this folder on my computer”). However, Python has its share of issues: it’s not easy to distribute your code, and the language itself isn’t as “pure” or “clean” as Scheme: it’s object-oriented (class-based) but also tries to be functional.

JavaScript is the programming language of the Web: almost every website you visit has some JavaScript on it. It’s functional, and it has prototyping OOP. It resembles Scheme in a lot of ways. However, it is often criticized for a really weak type system (you can add two lists and get a string as a result). Though it has flaws as a language, it is worth learning for its versatility: it runs on anything that has a web browser (phones, laptops, televisions, watches, toasters). You can make games with the

<canvas>element, and even use Node.js to run servers on your local computer (like Python). The blog you are reading this post on runs on is compiled by JavaScript. There are tons of libraries out there—-don’t bother to learn jQuery or React or any other “framework” when you’re getting started. Learn to manipulate the DOM manually, and you’ll discover that you don’t need a framework for most things.C is a low-level language, which makes it kind of messy to use. You need to manage memory on your own (people say it’s the difference between driving an automatic and a stickshift). However, it’s incredibly fast, and has some surprisingly elegant features. C teaches you how the insides of your computer really work. It also gives you access to a lot of low-level details like hardware and networking. Variations on C include C++ and C#, which add various features to C (for better or for worse). We recommend learning pure C to get started.

Java is an object-oriented language which was originally loved because, like JavaScript today, it ran everywhere. The language itself is very verbose—-it takes you a lot of code to get simple things done. We recommend only learning Java if you’re writing an Android app, or if you’re taking the AP Computer Science course (which, for a smart Scratch programmer, is pretty straightforward).

Should I take AP CS?

Yes. Take it if you have a free spot in your schedule, because you will probably breeze through the course. Don’t stress out too much about it. Use it as an opportunity to make friends with fellow CS students at your school and to get to know the CS teacher there.

If you don’t have a free spot, you could probably self-study it, but we see little educational value (it might look good on a college application?). You have better things to do.

Haskell is Scheme with a very powerful, “formal” type system. It is much easier to understand the concepts once you’ve used Scheme and Java a bit. We list it here only to warn how unintuitive it is at first and how hard it is to get practical things done with it (like printing to the screen), and to recommend Learn you a Haskell as a learning resource.

Here are some languages you shouldn’t care about:

CoffeeScript, TypeScript, anything that compiles to JavaScript: Don’t use one of these unless you really feel the need for a particular language feature. Certainly make sure you know JavaScript really well before, because all these languages tend to be thinly-veiled JavaScript once you really get into them.

Blockly, App Inventor, Greenfoot, Alice, LOGO, GameMaker, other teaching languages: unless you have any particular reason to use one of these languages, you will probably find it too easy: they are designed for beginners, and won’t give you the flexibility or “real-world” experience you want.

Rust, Go, anything owned by a company: not because the language has any technical flaws, but because of “vendor lock-in”: you don’t want your code to be at the mercy of whatever a private company decides to do with the language. Languages that have been around for a while tend to stick around. Go for a language that has more than one “implementation”, i.e. more than one person has written a competitive interpreter or compiler for it. This helps ensure that the standards are followed.

PHP: PHP is not a great language. The only time the authors use PHP these days is when trying to exploit badly-written PHP code in computer security competitions.

Perl, Ruby, Lua: Perl has essentially been replaced with Python in most places: a good knowledge of the command line and Python are far more useful to you. We haven’t seen any new exciting software written in Perl in a while. Ruby also resembles Python in many ways—-many say it’s much prettier—-but it’s known to be slower. It’s not as widely-used, but there exist big projects that do (Homebrew and Github are both Ruby-based). Same for Lua: it’s a nice language (Ruby’s syntax meets JavaScript’s prototyping OOP), but it isn’t used by enough people. Languages like this tend to be harder to find documentation, help, and working examples for.

Esoteric languages: these are written as jokes. You should be creating new ones, not programming in existing ones!

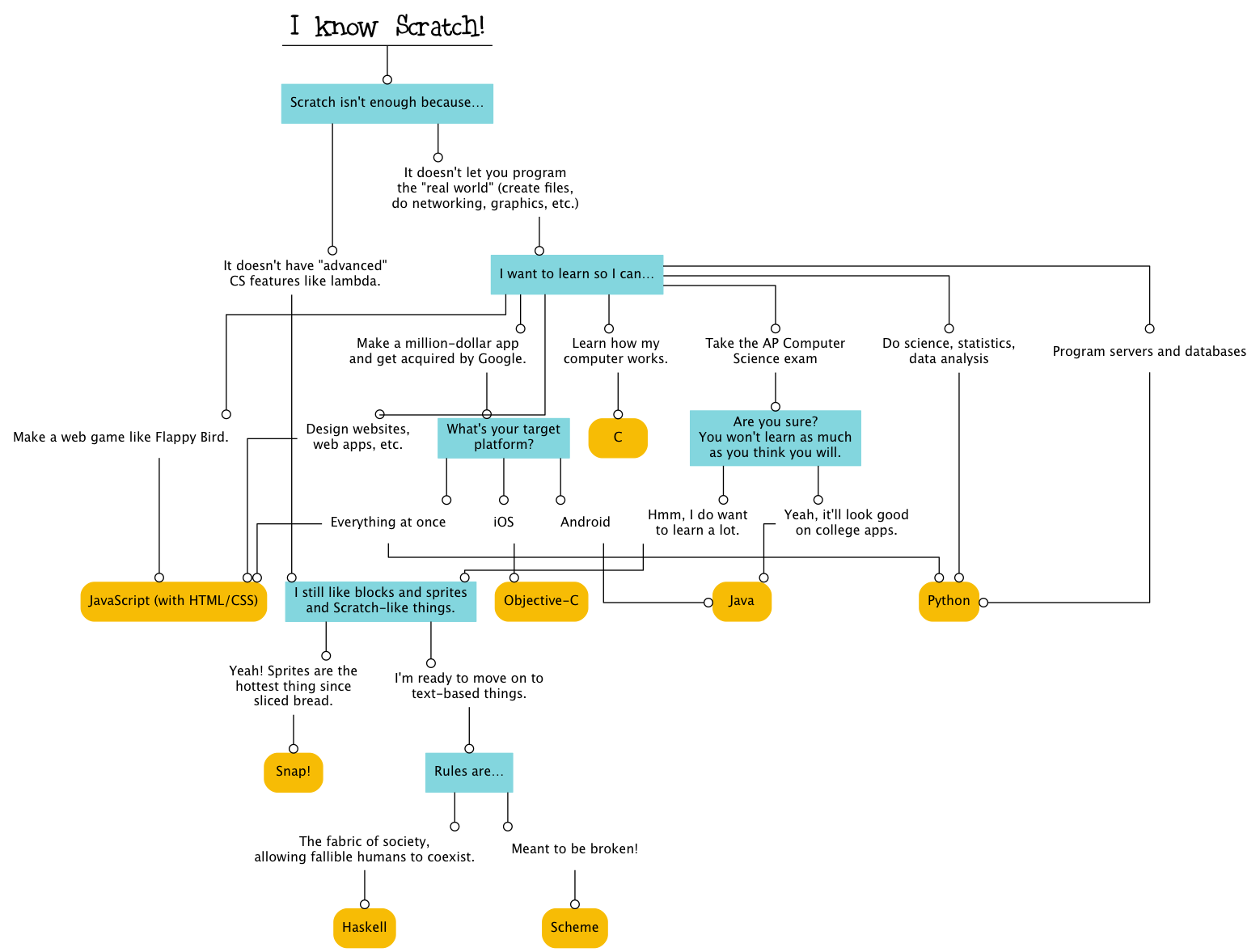

Still confused? Here’s a flowchart to help you out (click for a large SVG):

Finally: your personal experience and preference is far more important than anything we say. We cannot recommend a practical language any better than one you are already productive in (pedagogical languages, however, are a different deal).

So we’ve come a full circle: collect paradigms, not languages.

Tools of the trade

Programmers in the Real World™ are very dependent on their tools. In fact, though we don’t recommend it, most people define themselves by their tools.

This is largely because many of the more established tools in the CS world have a very steep learning curve (because they were written by lazy hackers who want to minimize keystrokes).

Here are our recommendations for what to invest in.

A text editor: Text editors are sacred, because in theory they’re the tool we spend the most time using. We can’t really recommend one because whatever we say, we’ll face lots of heat from supporters of some other one. Instead, here’s a short list of editors you might consider. All of these are free and available for Mac/Linux/Windows.

Atom: This editor was created by the GitHub team. It’s hugely customizable, with hundreds of themes and packages written by people. Atom is notoriously slow, though, because it essentially loads an entire web browser for its GUI. Cousins of Atom are Brackets by Adobe (just as slow, fewer packages) and Sublime Text (faster and prettier).

Tip from

technoboy10: Oodles of packages are available, but don’t try to use all of them. Find a few that really improve your coding workflow and use those.Vim: Vim is one of the oldest and most well-known text editors—-if you’re on a UNIX, you already have it installed. It runs in the command line, and requires you to learn several key-combinations to get started. It really is worth it, though, because Vim is amazing for productivity. In addition, several other applications use Vim-style keybindings. It’s an informal standard.

Tip from

hardmath123: trying to learn Vim? Write a blog post entirely in Vim. Maybe just stay in insert mode for the first hour. Usevimtutorto get started.Emacs: Like Vim, it runs in the command line and has a nontrivial learning curve. Unlike Vim, it is anything but lightweight. You can use Emacs to check your email, play tetris, and get psychiatric counseling (no joke). Vim and Emacs users are old rivals. See this comic for details.

The command line: learn to use bash from your terminal. It is extremely

empowering. The command line is the key to the insides of your computer, and

turns out to be surprisingly easy to get started with. Start with simple

operations like creating (touch) and moving (mv) files. Use less to read

them, and use pico or nano (or vim!) to edit them. Along the way, learn

important components of the UNIX

philosophy by piping programs

to each other. Learn how to use regular expressions with grep; this is

life-changing because regular expressions show up in every language and give

you a lot of power over strings. Figure out how to use man pages and

apropos to get help. Soon you won’t be able to live without the command line.

Git: For better or for worse, the most popular way for you to share code

these days is using a website called Github. Github is a

web interface for a tool called git, which is a version control software

(another one is hg, a.k.a. Mercurial). git lets you keep track of your code

as it changes, and lets other people contribute to it without having to email

different versions of code around. It’s not that hard to learn, and you’ll need

to learn it if you want to contribute to any projects these days.

Tip from

hardmath123: Don’t worry if you don’t truly grokgit. It’s my personal hypothesis that nobody really understands it. Just have enough working knowledge to get stuff done.

IRC: IRC or Internet Relay Chat is a decentralized chat protocol, which

means it’s like Skype except not controlled by any one company. It’s been

around for a while—it was used to organize a 1991 Soviet coup attempt. You

want to learn to use IRC because it’s not very intuitive at first look. But

many communities in the tech world communicate through IRC chatrooms, called

“channels”; it’s a great way to reach out and get help if you need it. The best

way to get into IRC is to just dig in—use Freenode’s

webchat client at first, then experiment with

others (Weechat, IRSSI, IRCCloud, etc). Feel free to say hi to us: we’re

hardmath123 and tb10 on Freenode.

Find (good) documentation: know about StackOverflow, Github, MDN, etc. We won’t drone on about these sites. Just know that they exist.

Tip from

technoboy10: Google is a coder’s best friend. Everybody has a different way of finding solutions to programming problems, but learning to search and find answers online is an immensely valuable skill. If you’re not a fan of Google, I recommend the DuckDuckGo search engine.

Folklore and Culture: some reading material

The CS world, like any community, has its own set of traditions. It’s said that UNIX is more an oral history than an operating system. With that in mind, here are some books, articles, and websites for you to peruse at your leisure.

Don’t take any of them seriously.

(Disclaimer—-some of these may have PG-13-rated content.)

- The Jargon Files

- How to be a hacker

- The UNIX-Haters’ Handbook

- Folklore

- Webcomics:

- xkcd

- Commitstrip,

- Geek&Poke (read these mainly to keep up with inside jokes)

- The Soul of a New Machine

- DEC wars

- Telehack (tell

forbinthathmsays hi) - Cryptonomicon

Parting words

You’re about to start on a wonderful journey. Enjoy it. Make friends. Make mistakes. These choices are all meaningless; you’re smart and you’re going to be alright no matter what text editor you use or which language you learn.

Hack on!